Born in the seaside town of Southend-on-Sea in Essex, in the United Kingdom, artist, designer, and wildlife photographer Jade Cave, 34, now calls Parkland home.

First moving from the U.K. to California when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Cave and her husband, Mark, a businessman, hit the road. They traveled 3,000 miles coast-to-coast, stopping in Arizona at the Grand Canyon National Park, Kartchner Caverns State Park, and the city of Tombstone, and of course, they visited the London Bridge in Lake Havasu City.

Arriving in Miami, they rented a house in Hallandale Beach, but it was love at first sight once they discovered the city of Parkland. “I found where I want to be,” Cave says. “It’s so beautiful here; I love all the nature.”

Growing up, Cave’s family had a home in South Africa, and they traveled there often, taking in the wildlife on safari. “Being blessed to have a house in South Africa, to have a connection with nature and experience amazing landscapes, I’ve always had a passion for the outdoors,” Cave says. The climate and landscape of Florida and the Everglades ecosystem are reminiscent to her of Africa.

With her D850 Nikon camera, Cave frequents Everglades National Park, the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge and the Green Cay Nature Center & Wetlands in Boynton Beach, and Wakodahatchee Wetlands in Delray Beach, where she captures birds, alligators, butterflies, and the flora and fauna.

“I love being outdoors in nature and being in the moment,” says Cave, who coincidentally was born on Earth Day.

Her photograph of Bunker, the Parkland burrowing owl who lived in her community on the 18th hole at the Parkland Golf and Country Club, is on display at the British Consulate in Miami. Another, a close-up of a long-neck white swan, titled “Reflections,” from her “Glades on Glass” collection, captures the bird with its long, S-shaped neck dipping into the water, its image reflected back.

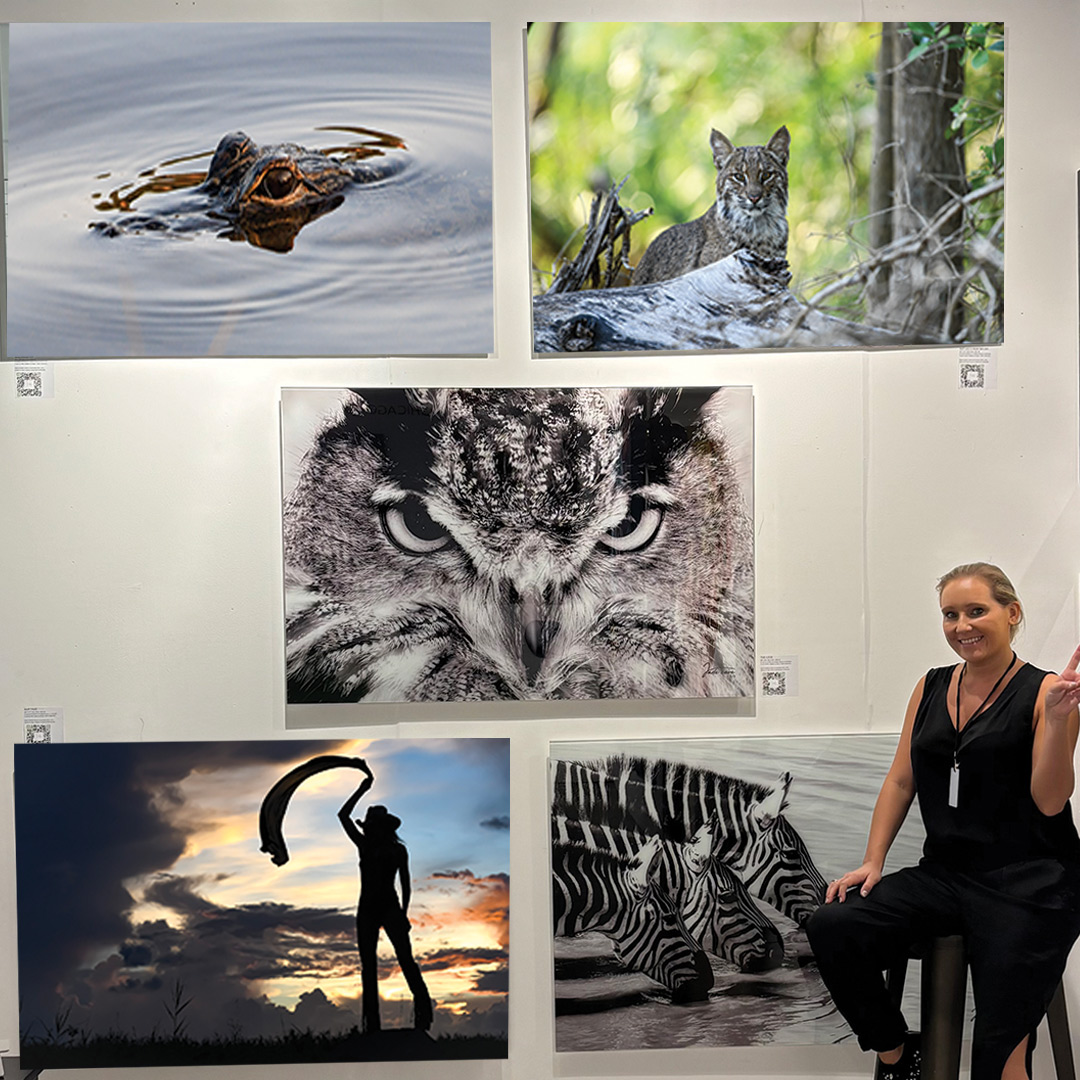

One of her favorite images is a head-on close-up of “Fluffy,” an alligator who is anything but. To capture the image, Cave waited and watched patiently. After five hours, Fluffy jumped and the waters parted.

Cave’s camera clicked, and she caught the shot of the day—the waters rippling around Fluffy’s giant head, his black eyes glistening in the water and his gaze staring intently at the viewer. “I love the way I captured the water moving around its face and the way the eyes stare at you,” she says.

Once she captures the shot, Cave feels elated. “When I look at my work, it takes me right back to the moment and I get an adrenaline rush,” she says. “It’s quite exciting and rewarding.”

She especially loves capturing close-ups and the emotions of the animals. She often shoots in black and white to create a stronger presence or to highlight the texture of the animal’s features.

Her photograph of a baby monkey asleep in its mother’s arms, titled “Nap Time,” from the “Spirit of Africa” collection, is an example of this black-and-white technique.

Cave will use a zoom lens to capture an eye or to frame a face. “It enhances the details and affords a different perspective,” she says.

Self-taught, Cave honed her technique by watching YouTube videos. She rarely enhances her photographs or uses Photoshop and only edits them to crop or sharpen the image. “What you see is what you get,” she says.

Last November, Cave traveled to Tsavo West National Park in Kenya (“Africa is part of my spirit”), where she photographed monkeys, zebras, giraffes, and the African plains.

These images, along with ones she took in the Everglades at Flamingo Campground, were on display at the Spectrum Miami Art Fair last December during Art Week in Miami. She donated 100% of her profits to the Alliance for Florida’s National Parks, where she volunteers her efforts to raise awareness about the national parks.

“Jade exudes such positive energy,” says Lulu Vilas, executive director of the Alliance. “She can light up a room with her exuberance.”

The Alliance for Florida’s National Parks, which includes Big Cypress National Preserve, Biscayne, the Dry Tortugas, and Everglades National Parks, raises funds and awareness to support the programs and activities of these national parks.

“Jade is never happier than when she is out in nature photographing wildlife and watching people enjoy the natural world,” Vilas says.

“We’re fortunate to have her,” she says. “She is extremely talented and has a generous spirit.”

For Cave, being part of Art Week in Miami was a dream come true and a highlight of her career.

To celebrate becoming a U.S. citizen last August, Cave put her feelings into a creative photo shoot, hiring a model to dress as a cowgirl, representing the spirit of the U.S. The photograph, titled “Freedom,” depicts a model wearing a cowboy hat, her back to the camera, her left arm upraised swirling an American flag.

Shot in silhouette at the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, against a dramatic ombré sky of grays, blues, and oranges, the photograph speaks to themes of freedom and personal reinvention, reflecting Cave’s journey and her heartfelt connection to her subjects.

“It’s my homage to America and the freedom of America,” says Cave, who learned the Bill of Rights and the Constitution as part of her journey to becoming an American citizen.

She admires the work of Big Cypress National Preserve photographer Clyde Butcher and English wildlife photographer David Yarrow, and she had the opportunity to have dinner with Yarrow three years ago in Miami.

“He inspired me to keep pursuing what I love,” says Cave, noting that it was Yarrow who suggested she use a Nikon D850.

Now she encourages others to learn the craft as well as they can, to persevere and differentiate themselves by capturing their own vision.

While in school in England, Cave studied fashion design and fashion photography. In 2009, she won the young retail designer competition.

She also studied Rogerian person-centered existential therapy and applies those principles to artwork she creates, finding expression and meaning to create word art, sketching an image using quotes, phrases, or inspirational speeches of iconic moments in history.

Her whimsical drawings of the Beatles’ “Abbey Road” album cover is a testament to her ability to merge visual and verbal expression. Depicting the four Beatles crossing the iconic walkway, the words from their lyrics—“Take a Sad Song and Make It Better,” “Baby, You Can Drive My Car,” and “Can’t Buy Me Love”—define the images.

Dyslexic as a child, Cave felt ashamed not to read or write well, and she says, “Language was my enemy.” Now, she embraces words, and they have become her medium for transformation and self-expression.

Cave is happy that people like both her photographs and her word art enough to hang on their walls.

This fall, she will exhibit her work at Silver Spring State Park in Silver Spring, Fla., and has her sights set on future gallery shows.

“There is always something new to learn and the art is forever evolving,” she says. “This adds to the excitement of being a photographer.”

Cave is excited to see where photography takes her. “My work comes from my heart,” she says. “I take something in life and transform it into art as a way to project how I see things. I give others a different view of creation.

“That, to me, is what I call art,” says Cave.

Visit Jade Cave on Instagram or at jadecaveart.com.