There must be at least two considerations to label something as art. The first is … there must be the recognition that something was made for an audience of some kind to receive, discuss or enjoy. … The second point is simply the recognition of skill.”

Brannon McConkey

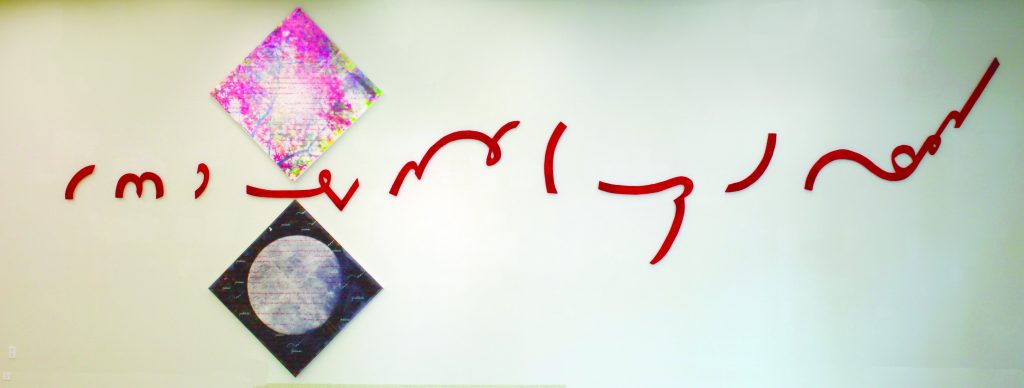

At Stacey Mandell’s first solo exhibition, Letters to Our Younger Self, at the Miami Dade College Hialeah Campus Art Gallery, there could be no doubt in a viewer’s mind the artist was sharing, successfully, the way she experiences the world and that her work was an extension of her personality. Her unique art form encompasses words, emotions, culture, but also activities of daily life and current events.

Mandell uses shorthand words and phrases — whether actual Gregg shorthand, cursive writing, even Braille — as an abstract gestural form, in which the form’s meaning provides an abstract narrative on the canvas.

“I believe we have much more in common than we may think — love and gratitude, diversity and inclusion, identity and culture, encourage and nurture. Saying ‘please’ and ‘thank you,’” Mandell said. “These are expressions of the soul. We all share the same hopes, dreams, and fears. We all have good days and bad days.

“My artwork is the physical manifestation of the expressions of my soul,” she said. “My messages are the conversations contained in the artwork.” xhibition curators Noor Blazekovic and Alejandro Mendoza, in a joint statement, said they were fascinated how Mandell frames an idea and communicates it to an audience. “What sets her creative work apart from other human expression is that she is creating in the world of non-verbal communication — she uses different tools: shorthand, words, visual images, movement, ideas, and more — to create feelings, thoughts, images, and ideas in the audience to communicate her particular message that as creator she wants to share. The intent is to inform, move, and open the audience’s mind and perspective to seeing the world in a different light than before.”

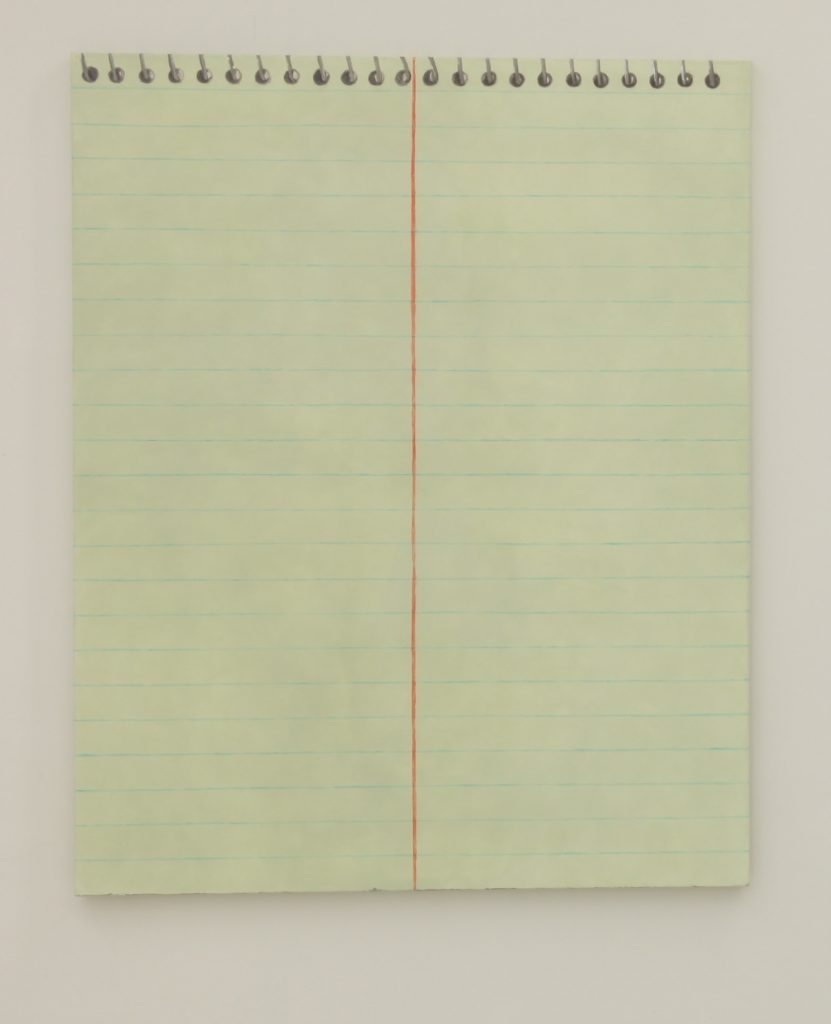

One work that shows that “different light” is This is not a blank Steno pad, a 5-foot-high acrylic-on-canvas image of the familiar off-green paper notebook. We may know it’s called a steno pad, and many of us of a certain age understand these notepads, with the spiral at the top for easy page-flipping, were popularized in their use by actual stenographers — secretaries, court reporters, close-caption writers in yesteryear’s TV industry, and the like.

Mandell has more than a passing familiarity with proper penmanship. A devotee of punctilious handwriting since her mother taught her cursive in grade school in rural central Illinois, Mandell made her way in the world — in quite the circuitous way, as it turned out — depending on Gregg Shorthand. After graduating from college prepared to teach music and math, Mandell instead took a clerical job where she had to learn shorthand.

“Learning Gregg Shorthand was a turning point on my career path,” Mandell said. From there, she became a legal secretary and, later, jumped to law school, employing her shorthand skills at every point.

“Throughout my 20-year legal career, I utilized shorthand to take notes and draft documents,” Mandell said. During that span, she said, she became fixated on using shorthand to communicate different ideas in a very different way — to express herself as an artist.

Once she left lawyering behind and relocated to South Florida when her husband retired, Mandell decided to pursue that idea.

This is not a blank steno pad was her first work in her steno pad series. It’s as much a statement about her present as it is about her view of our present culture: Much like the absence of ink and scrawl on Mandell’s canvas, the very jobs it represents — or, at least, the job titles — are now part of the past.

Mandell’s steno pad is blank, she said, “because of technology; no one uses it for its intended purpose anymore. It represents the dying art of a beautiful, phonetic language.” Mandell said after she painted the pad of paper, she’d planned to add to it a number of life lessons — in shorthand, of course. “But every time I thought about writing on it, I stopped. I could not bring myself to write on this one,” she said. “I finally realized this one meant more than anything I could express with shorthand.”