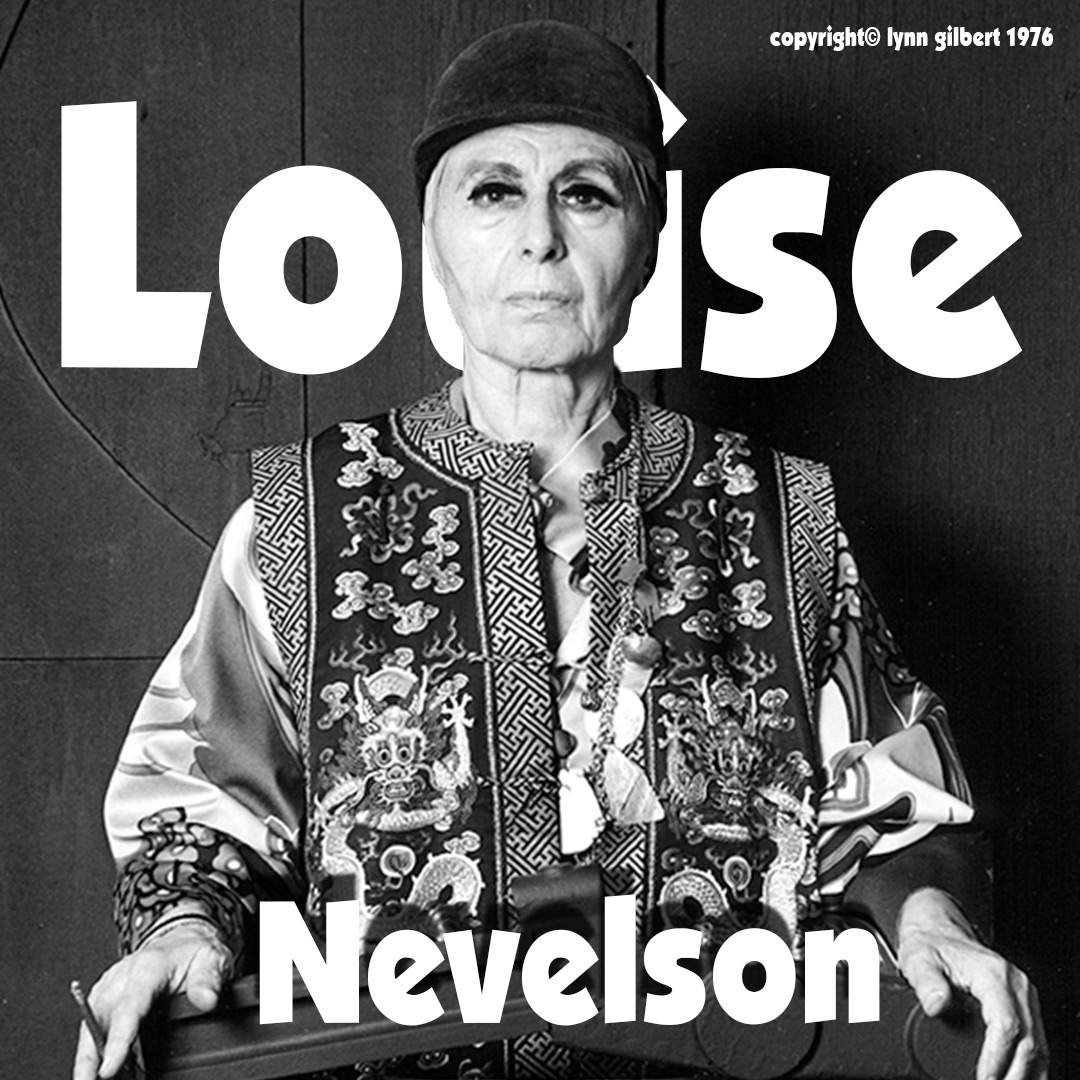

“I fell in love with black; it contained all color. It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors. Black is the most aristocratic color of all. … You can be quiet, and it contains the whole thing.”

—Louise Nevelson

American sculptor Louise Nevelson (1899–1988), known for her large, three-dimensional, wooden structures, worked primarily in monochromatic black or white.

Born Leah Berliawsky to Jewish parents in the Soviet Empire in 1899, she emigrated to the U.S. with her family when she was a child.

Growing up in Rockland, Maine, Nevelson moved to New York City to attend high school, where, after graduation, she got a job as a stenographer in a law office and met her future husband, Charles Nevelson, owner of a shipping company.

Calling herself “the original recycler,” Nevelson combed the streets of New York salvaging found objects, wood pieces, and other discarded items to use in her sculptures.

During the mid-1950s, she produced her first series of all-black wood landscape structures, describing herself as the “Architect of Shadow.”

“Shadow and everything else on Earth actually is moving,” she said at the time. “Movement—that’s in color, that’s in form, that’s in almost everything. Shadow is fleeting. … I arrest it and I give it a solid substance.”

Her sculpture titled “Shadow Chord,” created in 1969 and now at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, where it was just restored, was created at the height of her artistic career and embodies the visual language of her work with complex wood assemblages and monochromatic color.

Consisting of stacked boxes completely covered by her signature flat black paint, the sculpture gives this installation the imposing presence of a cityscape that alters the viewer’s perception of light and space.

At the museum since 2001, the work was in need of repair. The restoration was funded by a grant from Bank of America’s Art Conservation Project, a global program providing grants to nonprofit cultural institutions to conserve historically or culturally significant works of art.

Since it began in 2010, the Art Conservation Project has funded the conservation of individual pieces of art through more than 237 projects in 40 countries across six continents.

Among the 13 museums in the U.S. that were awarded the grant this year, the Boca Raton museum is the only one in South Florida to be chosen.

“The Boca Raton Museum of Art is honored to receive this prestigious grant from the Bank of America Conservation Project,” says Irvin Lippman, the museum’s executive director. “Nevelson’s sculpture commands a singular position in our galleries, and we are grateful for this support for its restoration.

“With its engulfing, sensuous environment full of shadows and mystery, this artwork continues to be a favorite for our visitors,” Lippman says.

Nevelson studied painting, voice, and dance at the Art Students League in New York City and held her first solo exhibition in New York in 1941. Over the next several decades, she became a pioneer in large-scale installations, an uncommon achievement for women of her generation.

Nevelson, whose marriage to her husband ended when she was 42, struggled financially much of her life. It wasn’t until her early 70s that Nevelson focused on monumental outdoor sculptures, after being commissioned by Princeton University in 1969 to create a large-scale sculpture for them.

To this day, she is most known for her wooden, wall-like, collage-driven reliefs consisting of multiple boxes and compartments that hold abstract shapes and found objects from chair legs to balusters that she collected from items discarded on the streets.

Nevelson is also the first woman to gain fame in the U.S. for her public art. In 1978, New York City created a sculpture garden, titled Louise Nevelson Plaza and located in Lower Manhattan, to showcase her sculptures. It became the first public space in New York City to be named after an artist.

Her works are in the collections of major art institutions around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., the Tate in London, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

The newly refurbished sculpture is currently on view on the second floor at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, 501 Plaza Real. Visit BocaMuseum.org.